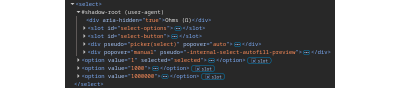

Each element can only have one shadow root. Some elements, including and , already have a built-in shadow root that is not accessible through scripting. You can inspect them with your Developer Tools by enabling the Show User Agent Shadow DOM setting, which is “off” by default.

Creating A Shadow Root

Before leveraging the benefits of Shadow DOM, you first need to establish a shadow root on an element. This can be instantiated imperatively or declaratively.

Imperative Instantiation

To create a shadow root using JavaScript, use attachShadow({ mode }) on an element. The mode can be open (allowing access via element.shadowRoot) or closed (hiding the shadow root from outside scripts).

const host = document.createElement('div');

const shadow = host.attachShadow({ mode: 'open' });

shadow.innerHTML = 'Hello from the Shadow DOM!

';

document.body.appendChild(host);

In this example, we’ve established an open shadow root. This means that the element’s content is accessible from the outside, and we can query it like any other DOM node:

host.shadowRoot.querySelector('p'); // selects the paragraph element

If we want to prevent external scripts from accessing our internal structure entirely, we can set the mode to closed instead. This causes the element’s shadowRoot property to return null. We can still access it from our shadow reference in the scope where we created it.

shadow.querySelector('p');

This is a crucial security feature. With a closed shadow root, we can be confident that malicious actors cannot extract private user data from our components. For example, consider a widget that shows banking information. Perhaps it contains the user’s account number. With an open shadow root, any script on the page can drill into our component and parse its contents. In closed mode, only the user can perform this kind of action with manual copy-pasting or by inspecting the element.

I suggest a closed-first approach when working with Shadow DOM. Make a habit of using closed mode unless you are debugging, or only when absolutely necessary to get around a real-world limitation that cannot be avoided. If you follow this approach, you will find that the instances where open mode is actually required are few and far between.

Declarative Instantiation

We don’t have to use JavaScript to take advantage of Shadow DOM. Registering a shadow root can be done declaratively. Nesting a with a shadowrootmode attribute inside any supported element will cause the browser to automatically upgrade that element with a shadow root. Attaching a shadow root in this manner can even be done with JavaScript disabled.

Declarative Shadow DOM content

Again, this can be either open or closed. Consider the security implications before using open mode, but note that you cannot access the closed mode content through any scripts unless this method is used with a registered Custom Element, in which case, you can use ElementInternals to access the automatically attached shadow root:

class MyWidget extends HTMLElement {

#internals;

#shadowRoot;

constructor() {

super();

this.#internals = this.attachInternals();

this.#shadowRoot = this.#internals.shadowRoot;

}

connectedCallback() {

const p = this.#shadowRoot.querySelector('p')

console.log(p.textContent); // this works

}

};

customElements.define('my-widget', MyWidget);

export { MyWidget };

Shadow DOM Configuration

There are three other options besides mode that we can pass to Element.attachShadow().

Option 1: clonable:true

Until recently, if a standard element had a shadow root attached and you tried to clone it using Node.cloneNode(true) or document.importNode(node,true), you would only get a shallow copy of the host element without the shadow root content. The examples we just looked at would actually return an empty

But for a declarative Shadow DOM, this means that each element needs its own template, and they cannot be reused. With this newly-added feature, we can selectively clone components when it’s desirable:

Option 2: serializable:true

Enabling this option allows you to save a string representation of the content inside an element’s shadow root. Calling Element.getHTML() on a host element will return a template copy of the Shadow DOM’s current state, including all nested instances of shadowrootserializable. This can be used to inject a copy of your shadow root into another host, or cache it for later use.

In Chrome, this actually works through a closed shadow root, so be careful of accidentally leaking user data with this feature. A safer alternative would be to use a closed wrapper to shield the inner contents from external influences while still keeping things open internally:

`);

this.cloneContent();

}

cloneContent() {

const nested = this.#shadow.querySelector('nested-element');

const snapshot = nested.getHTML({ serializableShadowRoots: true });

const temp = document.createElement('div');

temp.setHTMLUnsafe(`

const copy = temp.querySelector('another-element');

copy.shadowRoot.querySelector('#test').shadowRoot.querySelector('p').textContent="Changed Content!";

this.#shadow.append(copy);

}

}

customElements.define('wrapper-element', WrapperElement);

const wrapper = document.querySelector('wrapper-element');

const test = wrapper.getHTML({ serializableShadowRoots: true });

console.log(test); // empty string due to closed shadow root

Notice setHTMLUnsafe(). That’s there because the content contains elements. This method must be called when injecting trusted content of this nature. Inserting the template using innerHTML would not trigger the automatic initialization into a shadow root.

Option 3: delegatesFocus:true

This option essentially makes our host element act as a for its internal content. When enabled, clicking anywhere on the host or calling .focus() on it will move the cursor to the first focusable element in the shadow root. This will also apply the :focus pseudo-class to the host, which is especially useful when creating components that are intended to participate in forms.

This example only demonstrates focus delegation. One of the oddities of encapsulation is that form submissions are not automatically connected. That means an input’s value will not be in the form submission by default. Form validation and states are also not communicated out of the Shadow DOM. There are similar connectivity issues with accessibility, where the shadow root boundary can interfere with ARIA. These are all considerations specific to forms that we can address with ElementInternals, which is a topic for another article, and is cause to question whether you can rely on a light DOM form instead.

Slotted Content

So far, we have only looked at fully encapsulated components. A key Shadow DOM feature is using slots to selectively inject content into the component’s internal structure. Each shadow root can have one default (unnamed)

Fallback Title

A placeholder description.

A Slotted Title

An example of using slots to fill parts of a component.

Foo

Bar

Baz

Default slots also support fallback content, but any stray text nodes will fill them. As a result, this only works if you collapse all whitespace in the host element’s markup:

Fallback Content

Slot elements emit slotchange events when their assignedNodes() are added or removed. These events do not contain a reference to the slot or the nodes, so you will need to pass those into your event handler:

class SlottedWidget extends HTMLElement {

#internals;

#shadow;

constructor() {

super();

this.#internals = this.attachInternals();

this.#shadow = this.#internals.shadowRoot;

this.configureSlots();

}

configureSlots() {

const slots = this.#shadow.querySelectorAll('slot');

console.log({ slots });

slots.forEach(slot => {

slot.addEventListener('slotchange', () => {

console.log({

changedSlot: slot.name || 'default',

assignedNodes: slot.assignedNodes()

});

});

});

}

}

customElements.define('slotted-widget', SlottedWidget);

Multiple elements can be assigned to a single slot, either declaratively with the slot attribute or through scripting:

const widget = document.querySelector('slotted-widget');

const added = document.createElement('p');

added.textContent="A secondary paragraph added using a named slot.";

added.slot="description";

widget.append(added);

Notice that the paragraph in this example is appended to the host element. Slotted content actually belongs to the “light” DOM, not the Shadow DOM. Unlike the examples we’ve covered so far, these elements can be queried directly from the document object:

const widgetTitle = document.querySelector('my-widget [slot=title]');

widgetTitle.textContent="A Different Title";

If you want to access these elements internally from your class definition, use this.children or this.querySelector. Only the

From Mystery To Mastery

Now you know why you would want to use Shadow DOM, when you should incorporate it into your work, and how you can use it right now.

But your Web Components journey can’t end here. We’ve only covered markup and scripting in this article. We have not even touched on another major aspect of Web Components: Style encapsulation. That will be our topic in another article.

(gg, yk)